There are many answers to the question of why we accept God's violence as part of our theology. We could talk about our perception of God's holiness or our theory about the cross or our concept of the afterlife. We could also consider the role that influential evangelists, pastors, and authors play in our understanding of the Bible.

In the end, though, all our answers come back to a fairly simple premise: We believe God must punish sin because that's what we read in the Bible.

It's there, plain as anything, in Lamentations 1.

Or so we believe.

For the LORD has punished Jerusalem

for her many sins.

— Lamentations 1:5b NLT

Why we accept divine violence is an important question to consider, but it’s not the most interesting question to ask first.

At the beginning of our journey on A Nonviolent God, a much better question is how.

How can we accept God's violence?

Daughter Zion's first cry

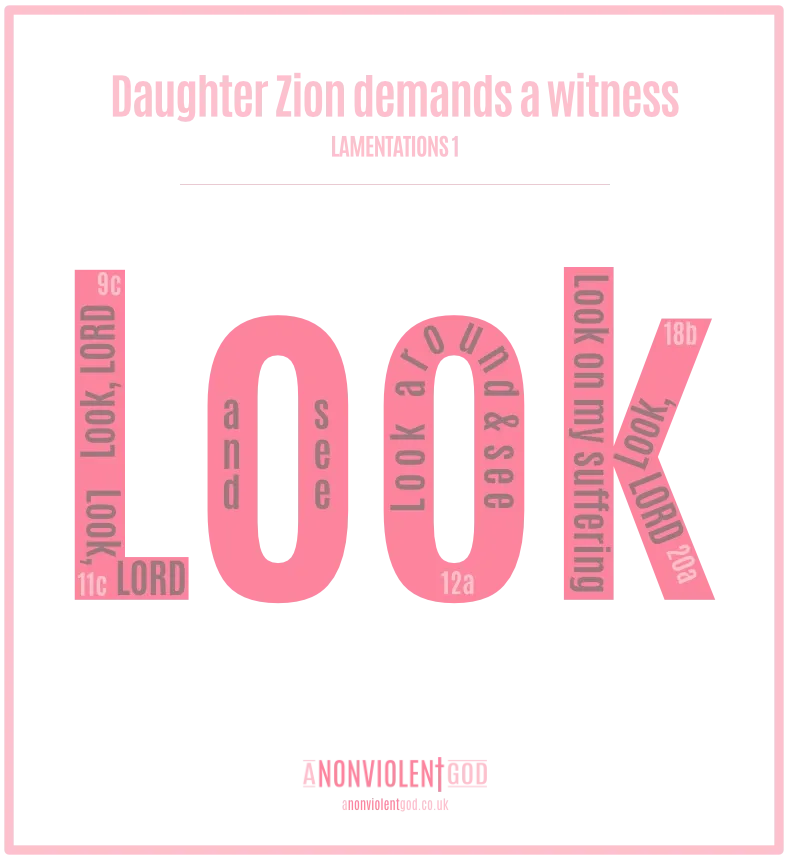

When Daughter Zion unexpectedly interrupts the reporter’s accusing narration in verse 9c, she does so with a single line. What would your first cry be here? What would your first cry be here?

Would you want to know where God was?

Would you cry out for answers about why this was happening to you?

Or would you cry out to God to save you?

Daughter Zion's cry therefore catches us by surprise. She wants none of those things. She simply wants to be seen by God.

"Look, LORD, on my affliction,

for the enemy has triumphed."

— Lamentations 1:9c NIV

[Daughter Zion] does not beg for relief, for vindication, or for restoration. She does not ask for the return of her children, for freedom, or for the return of past splendour. She asks only that God will look, see, take into consciousness what the enemy has done to her. She wants God to see her pain.

— Kathleen M. O'Connor

Lamentations and the Tears of the World, p.22

Daughter Zion's second interruption

When neither the reporter nor God responds to Daughter Zion's first cry, she interrupts the reporter again just two verses later.

"Look, LORD, and consider,

for I am despised.

Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by?

Look around and see."

— Lamentations 1:11c-12a NIV

She aims her first two cries to be seen (1:9c and 11c) at getting God to notice her suffering. When that fails to produce a response, she turns to the people passing by. “Look around and see,” she begs of them, desperate to be noticed (1:12a).

Daughter Zion fears people not seeing her pain. In verse 16, she openly talks about how she weeps because, "No one is near to comfort me, / no one to restore my spirit" (NIV).

Her fear is not one we share in our Western culture. Typically, we want as few people as possible to witness our vulnerability and pain. By privatising our tears we go uncomforted, and, if Daughter Zion is correct, our spirits go un-restored.

Daughter Zion's third interruption

By the time that Daughter Zion interrupts for a third time, the reporter has mentioned three times that there is "no one to comfort her" (17a, see also 2a and 9b), and has twice declared her "unclean" (17c, see also 8c) and therefore untouchable by another Jew. This reinforces within her a sense of extreme isolation.

Her anguish is now so acute that any random stranger witnessing her pain will do.

"Listen, all you peoples;

look on my suffering."

— Lamentations 1:18b NIV

And then, just a few lines later, when no-one responds to her cries, she once more calls on God to see.

"See, LORD, how distressed I am!

I am in torment within...

— Lamentations 1:20a NIV

This last time, she is both “distressed” and in “torment” (1:20). She is in severe mental and physical pain and is desperate for God to notice. Yet God does not act or respond. She even waves her enemies’ sin in front of his face (1:21c-22b). If he won’t comfort her, perhaps she can motivate him to treat them in the same way he’s treated her. But still nothing.

Her sin receives punishment, while the ransackers of her city get away with theirs.

In verse 21a, she ends up echoing the reporter’s repeated refrain: “They heard my groaning / yet there is no one to comfort me” (ESV). The first poem then ends with her declaration that, “My groans are many / and my heart is faint” (1:22c NRSV).

Her consistent demands for a witness go unfulfilled, but she mentions here how “they” (1:21a) hear her groans. Who is she talking about?

Her enemies.

The irony of her situation is that her enemies hear her groans and rejoice in her downfall (1:21a-b), while God—the one who is supposed to be comforting her—remains silent.

There’s only one answer to how

Daughter Zion’s responses in this first poem appear in twelve verses, and in eight of them she complains about not being seen or heard.

Lamentations uniquely offers a place in Scripture for the testimony of a female victim. And in doing so, it reveals the only legitimate answer to how we can accept God’s violence: we ignore the victims.

Let's think about the story of Noah's Ark (Gen. 6-9) for a moment. God brought every oxygen-breathing creature (over 2.1 million species) to the brink of extinction by punishing human sin with a worldwide flood. All in order to punish human sin. Yet we do not see the victims of this flood—human or animal—because we concentrate on Noah’s family and the many pairs of animals which God saves.

We don’t ponder the death throes of billions of creatures drowning in the rising floodwaters for good reason. Because if we did, we would have to acknowledge how the flood is the most horrific act of violence ever perpetrated on earth. And three times, the Bible tells us God was responsible (Gen. 6:7 & 13; 7:4).

Unlike Noah’s Ark, Lamentations refuses to hide the scenes of terrible violence. The shocking and gory aftermath of Jerusalem being destroyed by an invading nation who slay or enslave or starve the city's people is openly shared, especially at the end of Lamentations 2 and throughout chapter 4.

Yet, even though we know this is a war-torn city, we are still likely to nod along with the reporter and agree with his assessment that this violence has been "decreed" by God (17b) because of "her many sins" (5b).

This causes us to share the reporter’s lack of empathy and, instead of denouncing the violence of the Babylonians or holding them responsible, we too end up blaming the victim.

Our theology causes us to ignore the suffering of Daughter Zion and the people she poetically represents.

But Lamentations doesn't let us look away

"See me."

"See me."

"See me."

"See me."

"See me."

A brief de-tour into the Hebrew

Daughter Zion asks for someone to look in five separate lines of the poem. Each time, she uses the Hebrew word rā'â.

Over two-thirds of the time in the Old Testament we translate rā'â as "see," "saw," "seen," "sees," "seeing," "look," "looks," "looked," or "looking." It clearly means to perceive visually.

In Lamentations 1, the NIV translates rā'â as "look" (9c, 11c, and 18b) and "see" (12a and 20a).

Twice, in 11c and 12a, Daughter Zion adds a second Hebrew word nābat that also means "to look at" or perhaps even "pay attention to" or "gaze at." The NIV translates nābat in Lamentations 1 as "consider" (11c) and "look around" (12a).

The addition of nābat, a word that essentially means the same as rā'â, emphasises her demand for a witness.

It's like she's saying, "Look, really look."

There's even more going on here

Daughter Zion's repetition of rā'â ("look") would have reminded this song of sorrow's original audience of another story in the Bible where rā'â's use is prominent: the book of Exodus.

The Israelites groaned in their slavery and cried out, and their cry for help because of their slavery went up to God. God heard their groaning and he remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and with Jacob. So God looked (rā'â) on the Israelites and was concerned about them.

— Exodus 2:23-25 NIV (emphasis mine)

God hears both the Israelite’s cries and their groans, remembers, and then “looks” (rā’â). His concern for his people's mistreatment at the end of Exodus 2 turns into action within a matter of verses at the start of Exodus 3.

The LORD said, "I have indeed seen (rā'â + rā'â) the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians... And now the cry of the Israelites has reached me, and I have seen (rā'â) the way the Egyptians are oppressing them."

— Exodus 3:7-9 NIV (emphasis mine)

"I have rā'â rā'â the misery of my people..." The double-whammy of rā'â emphasises that this is a God who really sees and deeply cares for those being abused.

Daughter Zion wants God to see her and her suffering, because she believes that if he properly looked upon her, he would see the error of his ways and comfort her.

With each cry for God to look (to rā'â), Daughter Zion is pleading with him to remember himself. She needs him to remember that he is a liberator of those suffering oppression, not someone whose actions cause oppression.

Lamentations subverts God's violence

We’ve traditionally stood in the reporter's place: condemning sin and accepting God's violent punishment of it.

But Lamentations, despite our first impressions, doesn't allow us to accept this viewpoint. Between the repeated refrains of missing comfort and Daughter Zion's five pleas for others to "look" upon her suffering, we are being forced to witness the humanity of those being punished.

By continuously pointing out the suffering it causes, Lamentations subverts God's violence. It makes us see—really see—the torment of the victims caught in God's wrath. Once this happens, it breaks God's punishment of sin out of the realms of the theoretical or theological and into the realm of empathy.

Can we accept a violent God when we truly witness the suffering of the people he pours his wrath on to?

I find my answer is no.

However, your answer might be it makes God's violence harder to accept, and that's a good place to be at. We're on a journey here and no-one is expecting you to change your beliefs overnight. It certainly didn't happen that way for me!

But perhaps your answer is yes. You still believe the reporter is correct and God is punishing sin. If that's you, just be aware that the reporter changes his mind in Lamentations' second poem. He ends up accepting Daughter Zion's side of the story and fighting on her behalf. But if we’re to have the same change of heart and belief that the reporter undergoes, we need to talk about Deuteronomy first.